At all times, headwears had particularly practical functions, and were more a necessary number, than an accessory. Kerchiefs and wraps were aimed to protect of sunburns, hoods - of rain and wind, and helmets - of smashing enemy’s sword. And such tendency were last in Early Middle Ages through the XII-XIII centuries.

About then, different men’s and women’s headwear began to appear - hats, caps, berets. Common hoods also gained individual meaning as replacement stuff. Caps with “two-horned” cut with flowing veil were the most popular among the ladies.

New style of headwears were developing and modifying all over Medieval Europe. But exactly in Burgundia in the XV century, all the novelties were destined to be developed to the unprecedented pomp, throwing in the shade with its extravagance and bizarrerie not only headwears of foretime, but also of the upcoming centuries. Luxury of workmanship distinguished the clothing of court nobility at the times of Philip the Good and his successor Charles the Bold, and considered as an example to emulate for European seigniors.

The most typical and recognizable feature of so called Burgundian fashion was extreme emphasizing of long, pointed and narrow forms, which are peculiar for directional perception of the Gothic style. Just enough to remember high thin steeples, pointed arches and elongated windows - the most distinctive examples of the Cothc style in architecture.

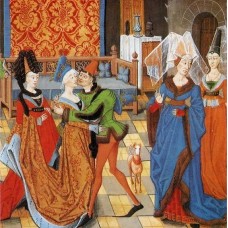

Illustration from manuscript “The Consolation of Philosophy”, Boethius, XV century, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, USA

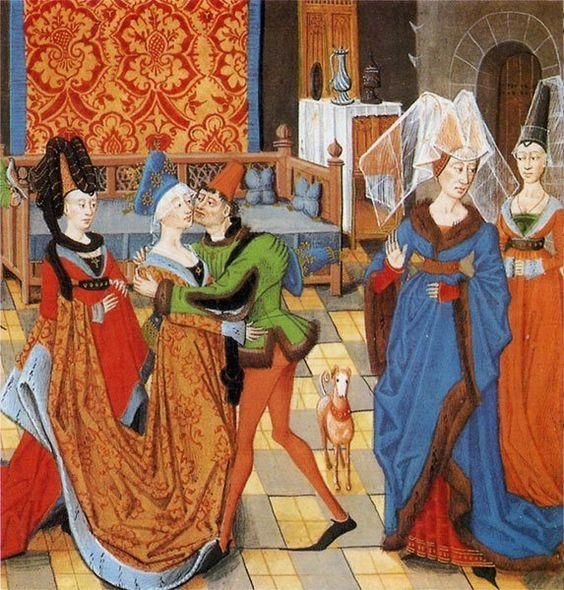

These forms were reflected in expressive Burgundian fashion. Really, the most exotic model of the women’s headwear were hennins - conical caps of enormous length. They were aimed to demonstrate social and property status of a woman and were making it perfectly. The more curule and rich a lady was, the longer head-dress she were wearing.

Hennins were being sewn of thick cloths, such as starched linen or on the frame of whale bone. Sometimes, hard paper was a base. Such base were covered with silk or expensive gold-and-silver damask, decorated with orfray and jewels. Thin transparent batist or gauze veil was attached to hennen/ If cloth were being twisted around the cone, it was called “atour”.

Besides, head-dress was decorated with long tail of thin silk, which had being draped in gorgeous pleats. Sometimes such drapery took bizarre forms. Specific frames had bing attached to hennin to shape fabric as sails or butterfly’s wings. A lot of noble ladies were dressed with two-horned caps, over which ornamented fabric had been flung on.

Illustration from manuscript Histoire de Helayne, unknown author, XV century French (1460-1465), Bibliotheque Royale, Brussels, Belgium

Such design were making women’s headwear not only long, simply immense widthway! Men were feeling themselves petty and tiny nearby the ladies, stalking along in huge hennins. Therefore, women had to do the knees bend not to catch door head, when entering.

Another popular Burgundian head-dress was escoffion. It’s shape was determined by hair-do: rollers of braids were set over the ears, and then being covered with golden hairnet, decorated with bed and pearls.

Illustration from manuscript “The Book of the Queen”, Christine de Pizan presenting her manuscript to Queen Isabeau of Bavaria, c. 1410 – c. 1414, British Library, London, UK

Forepart were covering the head up to forehead, and side parts were resting on the hairnets. Escoffion could be decorated with gem, brooch or bright feathers. Thin veil were often attached to the back side.

Head-dresses were so multivarious, so hair-does somehow went to the wayside. To emphasize elongation of forms even more, ladies were shaving not only eye-brows, but also hairs over the forehead. And uncovered back of the head allowed seeing the beauty of long neck.

Interesting detail is visible on the women’s portrays of that epoch: small loop of braid on the forehead was looked under any headwear. It was made for identifying of lady’s hair colour, because the rest of hais was hidden from prying eyes.

Certainly, all these tricks and defiantly extreme luxury couldn’t help but incurred Censura Ecclesiastica. But, the more monks were holding up to shame “diabolical horns”, the longer and fanciful hennins were.

Men’s headwears of Burgundia were holding their own in variety and riches of garniture. Firstly, hood was a part of lower-class outfit and usually was sewn to the main dress. In time, this headwear had been adopted by citizens, craftsmen and lately - even upper classes. Pelerine of hood was garnished with festoons or small bells (in a century, this attribute had become an integral part of motley coat). If tail was too long, men were tying it up. After a while, hood had become detachable, because men started to wear different headwears for one dress. Sometimes they even wore two hoods - one covered the head, and the second one had been thrown on the back.

Illustration from Terence’s “Comedies”, 1411 year, Library of Arsenal, Paris, France

Along with hoods, men were wearing caps, chapeau and copes of different cuts, under which white linen or cotton beguin had being worn. Such cales usually fit the head rather tight and were laced under the chin. Beguins were widespread in Burgundia and France at all, starting the times of crusades. A lot of graphical sources shows the knights, who wearing such caps unders the helmets, as it protected head and hair of the contact with helmet.

In this turn, chaperon was one of the most popular model among Burgundian nobles. Primarily, it had a shape of hood with pelerine (patte or cape) and long tail (also known as cornette, tippit or liripipe), covering the back of neck. There were a great variety to wear chaperon. For example, patte was tied on the top of head in a manner of cockscomb, and at the same time cornette were hanging down on the side or back. When required (for example, go before high rang person or during сhurch prayings), chaperon was removed and laid on the shoulder such a way, that patte was hanging from the back, and cornette - from the front.

Portrait of Louis II of Naples, Duke of Anjou, watercolour miniature, XV century, Louvre, Paris, France.

Another decoration of chaperon was a torse (wreath) - wide long ribbon, which were wreathed over the head, so chaperon looked like a turban. Some researchers guess, that torse was developed from the elongated cornette.

The torse in heraldic colours was also used by the knights. It was worn in a manner of wreath over the helmet. This way, the torse performed two functions: it was an identification mark for owner and also amortized hits in head.

Miniature from manuscript, Maître d’Orose (unknown medieval author), XV century, National Library, Brugge, The Netherlands

Chaperon was a part of class outfit. University professors and judges, for example, were wearing different model of chaperon. Generally, headwears strictly pointed at the occupation: doctor worn a beret, theologian - black velvet caps without brims, notaries worn beavers, and priesthood had to wear mitres and barrets - low, four cornered caps.

Dozens of styles and designs, using of felt, wool, straw, leather, cloths and other materials, amazing and fanciful shapes, fantastic splendid garbs - all these points allow considering Burgundian time as epoch of medieval fashion’s zenith.

As we can notice, XV century gave the world a great variety of original headwears, as a result of rampant imagination of Burgundy's grand people.

Steel Mastery will be glad to make an outfit of noble lady or dandy costume, which allow you immersing in the atmosphere of wonderful Middle Ages’ times! High hennin or puff chaperon will flesh out your look and you’ll be not left unnoticed at any festival, masquerade or another medieval event!

In this section you'll find different models of medieval headwears, which complete your outfit. If none of models are good for you, please send us the photo of the wished model with detailed description at [email protected] and we'll craft it for you.

We used some information and illustrations for this article from: Henry Shaw “Dresses and Decorations of the Middle Ages”, 1843; Margaret Scott “The History of Dress: Late-Gothic Europe 1400-1500”, 1980; Francois Boucher “20000 years of Fashion: The History of Costume and Personal Adornment”, 1987; Song, Cheunsoon and Lucy Roy Sibley “The Vertical Headdress of Fifteenth Century Northern Europe”, 1990; Sidorenko V. “History of styles in art and costume”, 2004 and everpresent web:) Pictures, not belonging to "Steel Mastery", are taken from the web. We do not pretend to be an owner of them and use them as illustrative example only.

0 Comments

Steel-mastery.com